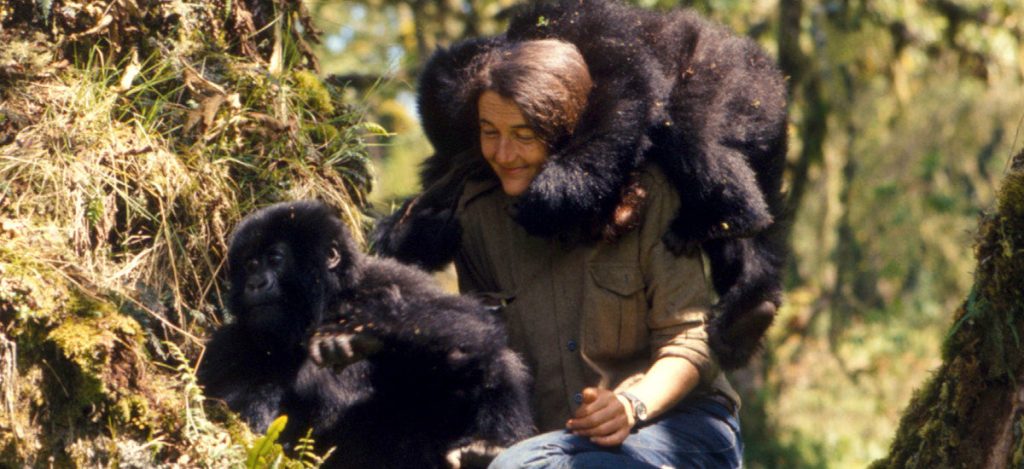

In the annals of modern conservation, a few names continue to shape global thinking. Dian Fossey is one of them.

Her work with mountain gorillas in Rwanda fundamentally altered the course of great ape protection in central Africa.

She arrived in the Virunga Mountains in 1967, at a time when poaching, civil instability, and indifference to wildlife dominated regional headlines.

The mountain gorilla population in the region was in visible decline. The species lacked both meaningful international advocacy and scientific understanding.

Fossey’s field research, conducted at high altitude in near-isolation, provided the first long-term observational data on Gorilla beringei beringei. But she wasn’t there for data collection alone.

She intervened directly, documenting killings, confronting poachers, and speaking with a clarity many found uncomfortable.

Moreover, her presence in Volcanoes National Park brought attention to a species most of the world had never heard of. Before conservation campaigns, before tourism circuits, and long before gorilla permits existed, there was Fossey and her notebooks.

Any serious engagement with gorilla tourism, wildlife policy, or primate conservation in Central Africa begins here. Fossey’s work laid the groundwork on which current interventions stand.

Early Life and Journey to Africa

Dian Fossey was born on January 16, 1932, in San Francisco, California. Her early years were marked by personal isolation and a strong attachment to animals. Horses, in particular, occupied her interest during adolescence.

She pursued veterinary studies briefly at the University of California, Davis, but later graduated with a degree in occupational therapy from San Jose State College in 1954.

By 1963, she was working at Kosair Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. That same year, she took a self-funded trip to Africa. It would change her life. While in Kenya, she met famed paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who was recruiting female researchers to study the great apes.

Dian Fossey joined a cohort that included Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas, though each worked independently.

In 1966, with Leakey’s support, she secured funding from the National Geographic Society and began planning a field study of mountain gorillas.

Her first attempt took her to the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), specifically to the Kabara region in Kahuzi-Biéga.

However, political unrest forced her out just months later. She was detained briefly by Congolese authorities and deported. Few would have returned. Fossey did—this time to Rwanda.

Establishing the Karisoke Research Centre

In September 1967, Dian Fossey established the Karisoke Research Centre. The name combined Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke, which flanked the site. Located at roughly 3,000 meters above sea level, the camp sat deep within Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park.

She began with two tents and a few local assistants. There was no running water, limited supplies, and no formal infrastructure. Fossey operated in near-complete isolation for the first months. It was deliberate. She aimed to observe gorillas without disturbing their patterns.

Daily tracking required several hours of trekking through wet montane forest. Over time, Fossey identified, named, and habituated several gorilla groups. One of the earliest males she studied was Group 4’s silverback, whom she named Digit in 1967.

Besides research, she monitored illegal activity. Poachers, traps, and signs of human intrusion were logged meticulously. Karisoke literally became an unofficial watchtower.

On top of that, Karisoke provided rare continuity. Unlike short-term visits by zoologists or tourists, Fossey remained in the field across seasons, witnessing generational shifts within gorilla families. She collected longitudinal data, something rare at the time.

If you ever visit the Virunga massif, you’ll find traces of that early camp still preserved. Not many field stations carry that kind of legacy.

The Threats to Gorilla Survival

By the late 1960s, mountain gorillas faced escalating threats in Rwanda and across the Virunga range.

Poaching was routine. Gorillas were killed for trophies, hands, or skulls sold to collectors. Infants were captured for illegal export to private zoos. Many died during capture or transit.

Wire snares set for antelope or buffalo often trapped gorillas instead. These crude devices cut deeply into limbs, sometimes fatally. Fossey documented such injuries in detail, including Digit’s eventual mutilation in 1977.

In addition, habitat pressure increased. Families displaced by regional conflict settled around the park’s periphery. Forest land was cleared for agriculture. Human-gorilla interactions became more frequent and more violent.

Tourism, too, introduced risk.

Though later regulated, early gorilla viewing expeditions were poorly managed. Disturbance, poor hygiene, and stress on the gorillas had serious health impacts.

Fossey saw no meaningful enforcement from local authorities. In her journals, she described patrols as symbolic. Real protection, she argued, required intervention. And that is what she did; on foot, in person, sometimes at personal risk.

You might ask, were these methods sustainable? Were they not more risky than impactful? That debate continues, but the threats she addressed remain relevant today.

From Scientist to Activist

Dian Fossey did not arrive in Rwanda to fight poachers. She came to study gorilla behaviour through daily contact and long-term observation.

But the circumstances she found dictated a transformation that we read of and see today.

After the killing of Digit in December 1977, Fossey shifted into confrontation. She formed active anti-poaching patrols composed of local staff and Karisoke assistants.

These teams destroyed snares, tracked poachers, and removed traps almost daily.

She then began collecting intelligence. Fossey paid informants to report illegal activity, sometimes directly confronting individuals suspected of harming gorillas. Critics called her methods aggressive. She called them necessary.

In addition, she lobbied governments, wrote to foreign embassies, and challenged international institutions that overlooked or contributed to gorilla trafficking.

The wildlife tourism sector, in particular, came under scrutiny. Fossey believed it prioritised profit over protection.

She established the Digit Fund in 1978, named after the gorilla whose death galvanised her mission. The organisation helped finance field patrols, veterinary response, and surveillance, years before such practices became standard.

Her publication Gorillas in the Mist in 1983 offered both a scientific record and a public warning. It reached a broad audience but also exposed her to backlash from parties invested in tourism growth or political stability.

You might find her approach difficult to replicate. Even now, conservationists debate where advocacy ends and activism begins.

Scientific Achievements and Conservation Impact

Dian Fossey’s fieldwork produced the first extended observational study of Gorilla beringei beringei. Her methods prioritised individual identification, long-term tracking, and non-invasive data collection.

She spent over 18 years documenting social structures, reproductive cycles, communication cues, and dominance hierarchies within mountain gorilla groups.

Her field notes, now archived, remain a critical reference for primatologists.

In 1983, she published Gorillas in the Mist, a combined field report and narrative summary. It became a foundational text in great ape research and later inspired a film adaptation. The book detailed everything from intergroup dynamics to maternal behaviour.

No other study had captured this depth before.

Moreover, her influence extended beyond primatology. Fossey’s work shaped protected area policies in Rwanda and inspired the creation of gorilla-focused veterinary and ecotourism models.

The data she collected enabled evidence-based management strategies that continue today.

On top of that, Karisoke became a training ground. It attracted visiting researchers, conservation interns, and international students.

Many of them later assumed leadership roles in conservation organisations.

Perhaps what you may not hear often is how she professionalised field research in the region. Her insistence on consistency, direct observation, and behavioural baselines changed how primates were studied in the wild.

Murder and Mystery – Her Death In 1985

On December 27, 1985, Dian Fossey was found dead in her cabin at the Karisoke Research Centre. The scene showed signs of forced entry.

Her skull had been crushed with a machete or heavy metal tool. There were no clear signs of robbery. Field equipment, cameras, and cash were untouched.

The investigation that followed was inconsistent. Rwandan authorities arrested her former tracker, Emmanuel Rwelekana, but later released him for lack of evidence. Months later, he was found dead in prison.

No formal trial took place. To this day, the case remains unsolved.

Moreover, various theories emerged. Some suggested retaliation by poachers. Others pointed toward internal staff disputes or local political motives. A few speculated about her opposition to certain tourism developments.

Theories multiplied as formal clarity diminished.

Fossey’s diaries, recovered from the site, contained scathing remarks about government officials, conservation agencies, and even colleagues. Her relationships with local authorities were strained.

With park revenue increasingly tied to tourism, her vocal resistance to gorilla visitation programs had made her a controversial figure.

In addition, she had begun refusing external grant offers tied to what she saw as compromised agendas. This reduced her institutional protection. By late 1985, she had few allies in formal conservation circles.

She was buried near Digit, her favourite silverback, in the small gorilla cemetery she had created behind Karisoke. The gravestone, etched simply with “No One Loved Gorillas More,” still receives visitors today.

As a reader engaging with this legacy, consider what her death reveals about the fragility of field-based conservation. Protection of wildlife, particularly when it disrupts revenue systems or threatens illicit networks, does not come without personal risk.

Conclusion

For anyone involved in gorilla conservation or planning a visit to Volcanoes National Park, the legacy of Dian Fossey is a structural context.

Her decisions shaped how gorilla tracking is governed, how populations are monitored, and how researchers, tourists, and communities engage with these protected forests.

Mountain gorillas remain vulnerable. The systems surrounding them—permits, patrols, veterinary units, tourism codes—exist because of foundational work done under pressure, often without support.

Today’s operational stability, including what you see on a well-guided trek, has roots in that contested past.

At Inmersion Africa Journeys, we approach gorilla experiences with the respect and preparedness they require. Every trek is coordinated in line with the conservation standards that Fossey helped inspire.

🔗 Submit an enquiry to begin a fully guided gorilla trekking experience that honours both species and setting.